” Yet Harlow’s ruthless interrogation brings her to the point “where I don’t see how to go further forward without going back” – all the way back to the day when, aged five, she was sent to stay with her grandparents and returned to find Fern gone and her family irreparably fractured. On starting at college, Rosemary “made a careful decision to never ever tell anyone about my sister, Fern. Her fearless nosiness knows no bounds and in no time she is drawing Rosemary out about her eccentric childhood and her missing twin. Rosemary returns to find Harlow comfortably installed in her room, having been thrown out by her boyfriend. Rosemary is dismayed: “What’s the point of never talking about the past if you wrote it all down and you know where those pages are?”īut the past is not so easily ignored. As she is about to return to college her mother makes an unexpected gesture: she wants Rosemary to have her old journals. Sprung from jail by her father, Rosemary flies home for the Thanksgiving holiday.

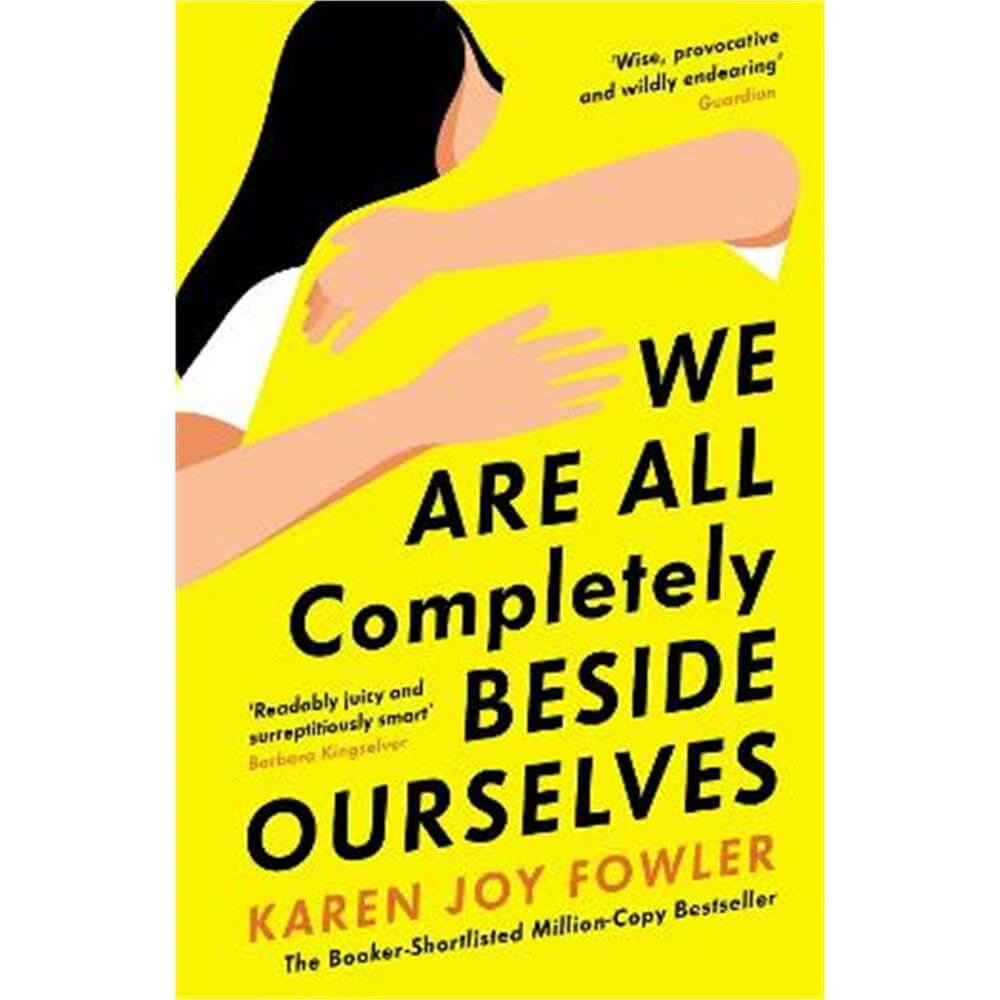

Yet there is a devastatingly calibrated shift of perception about a quarter of the way into the text. That makes it sound as though the value of Karen Joy Fowler’s seventh novel is predicated on its big reveal, or that it is some kind of superior thriller. It is hard to imagine a less apt description of her intricate, emotionally resonant and disturbingly funny account of sibling loss.

This is the first time I have reviewed a novel about which it is almost impossible to say anything without destroying the moment of jolting astonishment that I experienced on first reading it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)